Imaginary Ends

Aside from all the science fiction I consumed, when I was a child my favourite books were those in which children visited other worlds - not via spaceships, but by using magic. Although to be honest I didn't see that much difference between the two methods of travel in my mind and as far as I was concerned Narnia may well have simply been in a parallel dimension.

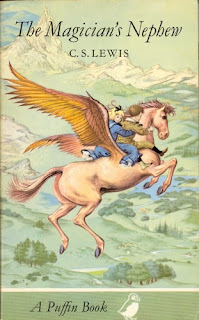

I particularly enjoyed the alchemical feel of The Magician's Nephew - there was something pseudo scientific about the whole method of travel between worlds, with the logic of the green and the yellow rings and the Wood Between the Worlds with its portals into other universes. Furthermore when Digory and Polly discovered Charn my SF heart leapt at the description of its sun as a red giant with small blue dwarf companion star; likewise at Digory catching a glimpse of Jupiter "quite close - close enough to see its moons" whilst travelling back to London from the Wood Between the Worlds.

As far as I was concerned these tales were all pretty much the same; whether you reached the new worlds using by wardrobe, spaceship, TARDIS or magic ring, the important part was what happened when you got there. And that could be anything.

The only differences between these stories seemed to be what happened at the end. The science fiction ones continued onwards and outwards - often in a spirit of optimism but sometimes with a dark dystopian message. The main thing about them was that they were open ended. The fantasy ones on the other hand often had contrasting conclusions. More often than not the children involved in the story had to return to the real world and in doing so somehow deny the experience they'd had there in order to grow up and move on.

I was devastated at the end of Jennie by Paul Gallico when Peter - having spent the bulk of the novel as a cat exploring London and Glasgow with his tabby companion Jennie - not only becomes a boy again but then proceeds to forget about the entire experience. To be honest I would much rather he'd stayed a cat - his parents were inattentive anyway - but if he did have to return to his normal life then at least let him remember his cathood. Anything else was just cruel. I burst into tears when I finished it, unable to bear the compounding of the whole "it was all just a dream" trope with it being a dream that the protagonist no longer even remembered. It's still a fantastic book though and perhaps that's why I felt so let down by the ending.

What's so great about growing up anyway? Who says you have to put aside childish things like the imagination and a sense of adventure? Aslan, that's who. Apparently after an adventure or two most children are barred from Narnia; their own lives in late 1940s or early 1950s England being more important.

I think it's important to hold onto the way you felt as a child, to hold onto the sense that anything's possible. The adult world hold enough sway over our lives already, is it too much to ask that we be allowed to hold on to our imaginations at least?

One of my favourite stories as an adult is Neil Gaiman's Neverwhere which put a modern spin on the child in a fantasy world idea by having the protagonist as an adult (albeit one who still sometimes played with toys). But the best part was the ending. Having spent the whole of the story trying to get his real life back, Richard succeeds only to realise that's not what he wants after all. His despair at not being able to get back into London Below is palpable, as is the relief when the Marquis de Carabas relents and invites him back (with the unspoken price "...and now you owe me a favour").

That was how it should be done.

There is something about the imaginary worlds we play in as a child that borders on reality, which is why these stories are so compelling. Our imagination was so strong back then. Remember those things that happened when you could fly or talked to a ghost or walked through a wall? Did they actually happen or was it only a game?

Maybe I'm wrong, but I don't see what's so great about being grown up if you have to give imagination up.

I particularly enjoyed the alchemical feel of The Magician's Nephew - there was something pseudo scientific about the whole method of travel between worlds, with the logic of the green and the yellow rings and the Wood Between the Worlds with its portals into other universes. Furthermore when Digory and Polly discovered Charn my SF heart leapt at the description of its sun as a red giant with small blue dwarf companion star; likewise at Digory catching a glimpse of Jupiter "quite close - close enough to see its moons" whilst travelling back to London from the Wood Between the Worlds.

As far as I was concerned these tales were all pretty much the same; whether you reached the new worlds using by wardrobe, spaceship, TARDIS or magic ring, the important part was what happened when you got there. And that could be anything.

The only differences between these stories seemed to be what happened at the end. The science fiction ones continued onwards and outwards - often in a spirit of optimism but sometimes with a dark dystopian message. The main thing about them was that they were open ended. The fantasy ones on the other hand often had contrasting conclusions. More often than not the children involved in the story had to return to the real world and in doing so somehow deny the experience they'd had there in order to grow up and move on.

I was devastated at the end of Jennie by Paul Gallico when Peter - having spent the bulk of the novel as a cat exploring London and Glasgow with his tabby companion Jennie - not only becomes a boy again but then proceeds to forget about the entire experience. To be honest I would much rather he'd stayed a cat - his parents were inattentive anyway - but if he did have to return to his normal life then at least let him remember his cathood. Anything else was just cruel. I burst into tears when I finished it, unable to bear the compounding of the whole "it was all just a dream" trope with it being a dream that the protagonist no longer even remembered. It's still a fantastic book though and perhaps that's why I felt so let down by the ending.

What's so great about growing up anyway? Who says you have to put aside childish things like the imagination and a sense of adventure? Aslan, that's who. Apparently after an adventure or two most children are barred from Narnia; their own lives in late 1940s or early 1950s England being more important.

I think it's important to hold onto the way you felt as a child, to hold onto the sense that anything's possible. The adult world hold enough sway over our lives already, is it too much to ask that we be allowed to hold on to our imaginations at least?

One of my favourite stories as an adult is Neil Gaiman's Neverwhere which put a modern spin on the child in a fantasy world idea by having the protagonist as an adult (albeit one who still sometimes played with toys). But the best part was the ending. Having spent the whole of the story trying to get his real life back, Richard succeeds only to realise that's not what he wants after all. His despair at not being able to get back into London Below is palpable, as is the relief when the Marquis de Carabas relents and invites him back (with the unspoken price "...and now you owe me a favour").

That was how it should be done.

There is something about the imaginary worlds we play in as a child that borders on reality, which is why these stories are so compelling. Our imagination was so strong back then. Remember those things that happened when you could fly or talked to a ghost or walked through a wall? Did they actually happen or was it only a game?

Maybe I'm wrong, but I don't see what's so great about being grown up if you have to give imagination up.

Comments