Sagan's Brain

When I was growing up it seemed to be a fairly common thing for children's heroes to be footballers. My friend Shamus expressed an admiration for Alan Ball although I suspected that this was just because his name was Ball. Shamus was obsessed with all things football related, so a footballer actually named Ball... well there was no choice really. It was lucky that the Arsenal centre forward Booty McGoalmouth was only a figment of my fevered imagination.

I didn't have such heroes. Football didn't interest me and I had no idea who Cyril was nor what his nice one entailed. My heroes were Michael Faraday, Albert Einstein, Doctor Who, Charles Darwin and Mr Spock. This meant that had I ever fallen into a coma my parents would have had a bit of trouble getting one of them to come to my bedside and try and rouse me seeing as they were either dead or fictional (although I expect Tom Baker would have given it a go in character).

However I did meet someone when I was twelve who, even though I had no idea who he was at the time, went on to become a hero. I had attended the Royal Institution Christmas Lectures once before when David Attenborough had delivered a series of lectures on the languages of animals when I had been eight; now I was going again as they were all about another subject that interested me to the point of obsession.

Space.

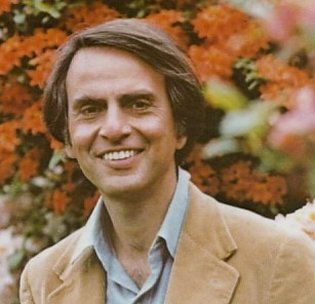

Or more specifically the planets. I hadn't heard of the lecturer before but found his manner engaging and friendly. Despite his humility and the way he talked without seeming to blow his own trumpet it became clear that he'd had a pivotal role in many of the unmanned NASA missions to the planets which at the time had just experienced a resurgence in activity with the Viking Landers on Mars and the launch of the Voyagers to the outer planets. His name was Carl Sagan.

The main thing I recall about him was his passion for the subject and how, when after one of the lectures I asked him a (fairly simple) question about rivers on Mars, he responded with a level of enthusiasm I would have thought more appropriate for a discussion with one of his peers about an exciting new discovery. But no, he was being enthusiastic to me because to him all "Yooman" minds were fascinating and worth engaging with and if they showed an interest in his interests then all the better. There was no impression of any sense of assumed superiority on his part - even though I was a child and he was one of the bigwigs at NASA I got the impression that had there been more time he would have been happy to sit down and listen to my childish waffling about space with interest and encouragement.

But this was him all over and something that is reflected in all his work. Over the next few years I devoured any Sagan I could get my hands on which back then consisted of only a handful of books; Broca's Brain which contained "reflections on the romance of science", The Dragons of Eden in which he pondered the evolution of human intelligence and The Cosmic Connection which discussed the possibilities of extraterrestrial life. I think it was the third of these volumes which most resonated with me as the thought that there were other beings out there who might one day swoop down to take me away from all this was a seductive one, even if it was symptomatic of an older and far less scientific way of thinking.

Then of course Sagan rose to far greater public prominence via Cosmos, a TV series exploring the entire history of creation and our place as sentient beings in it. Everyone watched as this scientific superhero dressed in his signature costume of brown jacket and rollneck top explored the universe in his starlike spaceship of the imagination and waxed lyrical about the history of human thought. He wasn't just interested in the universe itself but in these miniature reflections of it wandering around being sentient and in their attempts to make sense of it in their own way.

He was never dismissive or scathing about anything and kept an open mind, retaining a calm and reasonable patience about his demeanour that many politicians and television presenters might do well to learn from. The only time he appeared to come anywhere close to losing his cool was when he discussed the human capacity for self destruction and how the cold war might mean that we'd destroy ourselves before we discovered we weren't alone in the universe. Then his brow would darken and you'd get the distinct impression that he was talking to the young and urging them with all his might not to make the same mistakes their parents had made.

Another time he appeared to get slightly cross was when discussing Immanuel Velikovsky, a barking mad Russian astronomer who came up with a breathtakingly ridiculous theory which he published in the 1950s bestseller Worlds in Collision. This book was by all accounts a von Daniken-esque flight of fancy in which he postulates that conditions in the Solar System were more like a game of interplanetary bar billiards than nature's clockwork.

The strange thing was that Sagan wasn't getting cross with Velikovsky himself who was a frequent subject of passages in his books and in the Cosmos TV series. I suspect he picked such a ridiculous theory to critique in order to illustrate how important the scientific method is and how it needs to be applied even in cases such as this. His anger was directed more at the scientific community itself and their dismissive attitude:

By all means debunk the charlatans using pseudoscience to swindle the masses and the fraudsters using belief in an intangible and unreasonable god to control them, but please do so in a scientific and methodical manner. Possible until disproven is as important a tenet as Innocent until proven guilty.

It's not enough simply to call Velikovsky a twat.

I didn't have such heroes. Football didn't interest me and I had no idea who Cyril was nor what his nice one entailed. My heroes were Michael Faraday, Albert Einstein, Doctor Who, Charles Darwin and Mr Spock. This meant that had I ever fallen into a coma my parents would have had a bit of trouble getting one of them to come to my bedside and try and rouse me seeing as they were either dead or fictional (although I expect Tom Baker would have given it a go in character).

However I did meet someone when I was twelve who, even though I had no idea who he was at the time, went on to become a hero. I had attended the Royal Institution Christmas Lectures once before when David Attenborough had delivered a series of lectures on the languages of animals when I had been eight; now I was going again as they were all about another subject that interested me to the point of obsession.

Space.

Or more specifically the planets. I hadn't heard of the lecturer before but found his manner engaging and friendly. Despite his humility and the way he talked without seeming to blow his own trumpet it became clear that he'd had a pivotal role in many of the unmanned NASA missions to the planets which at the time had just experienced a resurgence in activity with the Viking Landers on Mars and the launch of the Voyagers to the outer planets. His name was Carl Sagan.

The main thing I recall about him was his passion for the subject and how, when after one of the lectures I asked him a (fairly simple) question about rivers on Mars, he responded with a level of enthusiasm I would have thought more appropriate for a discussion with one of his peers about an exciting new discovery. But no, he was being enthusiastic to me because to him all "Yooman" minds were fascinating and worth engaging with and if they showed an interest in his interests then all the better. There was no impression of any sense of assumed superiority on his part - even though I was a child and he was one of the bigwigs at NASA I got the impression that had there been more time he would have been happy to sit down and listen to my childish waffling about space with interest and encouragement.

But this was him all over and something that is reflected in all his work. Over the next few years I devoured any Sagan I could get my hands on which back then consisted of only a handful of books; Broca's Brain which contained "reflections on the romance of science", The Dragons of Eden in which he pondered the evolution of human intelligence and The Cosmic Connection which discussed the possibilities of extraterrestrial life. I think it was the third of these volumes which most resonated with me as the thought that there were other beings out there who might one day swoop down to take me away from all this was a seductive one, even if it was symptomatic of an older and far less scientific way of thinking.

Then of course Sagan rose to far greater public prominence via Cosmos, a TV series exploring the entire history of creation and our place as sentient beings in it. Everyone watched as this scientific superhero dressed in his signature costume of brown jacket and rollneck top explored the universe in his starlike spaceship of the imagination and waxed lyrical about the history of human thought. He wasn't just interested in the universe itself but in these miniature reflections of it wandering around being sentient and in their attempts to make sense of it in their own way.

He was never dismissive or scathing about anything and kept an open mind, retaining a calm and reasonable patience about his demeanour that many politicians and television presenters might do well to learn from. The only time he appeared to come anywhere close to losing his cool was when he discussed the human capacity for self destruction and how the cold war might mean that we'd destroy ourselves before we discovered we weren't alone in the universe. Then his brow would darken and you'd get the distinct impression that he was talking to the young and urging them with all his might not to make the same mistakes their parents had made.

Another time he appeared to get slightly cross was when discussing Immanuel Velikovsky, a barking mad Russian astronomer who came up with a breathtakingly ridiculous theory which he published in the 1950s bestseller Worlds in Collision. This book was by all accounts a von Daniken-esque flight of fancy in which he postulates that conditions in the Solar System were more like a game of interplanetary bar billiards than nature's clockwork.

The strange thing was that Sagan wasn't getting cross with Velikovsky himself who was a frequent subject of passages in his books and in the Cosmos TV series. I suspect he picked such a ridiculous theory to critique in order to illustrate how important the scientific method is and how it needs to be applied even in cases such as this. His anger was directed more at the scientific community itself and their dismissive attitude:

"No matter how unorthodox the reasoning process or how unpalatable the conclusions, there is no excuse for any attempt to suppress new ideas, least of all by scientists committed to the free exchange of ideas."

This is something I believe all scientists and people of a scientific bent should bear in mind. At all times we need to ask ourselves whether we are believing something because it is true or simply because we want it to be true. The latter is unscientific.(Carl Sagan, An Analysis of "Worlds in Collision": Introduction 1977)

"I'm a great fan of science, you know"

Problems can arise when science replaces other more irrational beliefs in people's minds. In an attempt to be enlightened and to better themselves some people adopt science, scepticism and atheism as religion substitutes, as something they can hold onto and which can provide a moral high ground from which the view of other less enlightened people gives them a wonderful sense of superiority. This is symptomatic of an older and far less scientific way of thinking.(Slartibartfast, The Hitch Hiker's Guide to the Galaxy, 1978)

By all means debunk the charlatans using pseudoscience to swindle the masses and the fraudsters using belief in an intangible and unreasonable god to control them, but please do so in a scientific and methodical manner. Possible until disproven is as important a tenet as Innocent until proven guilty.

It's not enough simply to call Velikovsky a twat.

Comments