Down the Tube 6: Via Imagination

Just as moving house had opened and closed the first book of my Tubehood, The Case of the Victorian Zodiac, so moving house once more at the close of the seventies would bring the second book, The Case of the Dism Rly, to an end and set the pieces up for the third and final book in the trilogy. We weren't moving far, just a mile or so down the road to Cranley Gardens. This was near Highgate tube and Highgate Wood (two of the primary locations of book two).

Nevertheless things were very different now. For a start I was growing up. Not only had I recently discovered the allure of spiky women in general and Toyah Willcox in particular which had put an entirely different spin on things, but I'd also moved up into the senior school.

This latter move was an extremely unpleasant one (at some point I will write a comprehensive blog entry explaining why), so suffice to say that I decided to continue concentrating on my inner life and as a result my enthusiasm for all things London Underground remained, albeit in a diminished form.

One of the best things about the location of Cranley Gardens was that it had been on one of the great lost lines that originally flowed outwards from Highgate. Imagine that; I was living in a road that had once had its own tube station but which was now derelict. I even worked out where the station had been.

Right up at the top of Cranley Gardens diagonally opposite one looming corner of Highgate Wood (still dark and primeval to me) and across from number 23 (which would become famous a few years afterwards for very different reasons) lay a garden centre. They were all the rage back then. Behind the garden centre was a sunken path.

The layout and feel of this path was very familiar to me from my earlier explorations of the hidden places in Highgate Wood. This was quite clearly the route of an abandoned railway, the unnatural curve of the path gave it away, the rubble of pumice underfoot. It disappeared off behind the houses through thick trees before rising above them on a viaduct that gave commanding views of East London and Essex. The route was lined with rusty metal signs warning of 50,000 volts amongst the weeds and stanchions that had obviously once carried cables, but like its cousin across in Highgate Wood, this Dism Rly had no actual sleepers or tracks, no real live rail despite the warnings.

Such was the unevenness of ground level in Muswell Hill that even after being so high up the track shortly afterwards found itself looking up at the backs of houses and shops on Muswell Hill Broadway before coming to a end at a pedestrian subway under Muswell Hill itself.

There was no sign of the actual stations themselves and from this point onwards it became difficult to follow the route to the terminus at Alexandra Palace. There was a school in the way for a start. If I wanted more I would have to look elsewhere.

Heading east from Highgate I soon discovered the rest of this ancient route curving round from the junction of Archway Road and Jackson's Lane, another stretch of abandoned railway bed that would one day become known as the Parkland Walk. Through cuttings and across narrow viaducts this route took in Crouch End station, the only place aside from the secret platforms at Highgate that still resembled a railway station. In some ways the discovery and pinning down of the solution to this childhood mystery was the end of the line for me. I could move on, although for years afterwards the route was one of my favourite walks.

But there was one place - in fact there still is one place - that the more mythical Tube has persisted. Inside my head. In dreams. Night dreams, not daydreams.

There's a somnambulant network there, reflecting but somehow far more exciting than the real thing could ever hope to be; in the dreamworld you don't need to get planning permission and as such things are bigger and better. Furthermore, these lines are all part of what appears to be a very consistent dream world (see earlier blog entry Dancing the Dreamscape for more detail of this).

There's a distant version of the western outreaches of the Metropolitan Line that takes days to get to and from. There are vast swathes of tracks filling an entire valley alongside the main route somewhere near Crouch End station, an idealised version of the stillborn branch line I discovered so long ago.

There are versions of the Circle Line in which the tracks run alongside mysterious caverns inhabited by strange manlike creatures; a Victoria Line that somehow manages to run as far south as Luxor in Egypt. And often there are dreams of the retooling of the whole network, vast building works threading myriad extra lines through the congested cats cradle of central London with complex new branches of the District Line sprouting like vines across the barren tubeless wastes of South London.

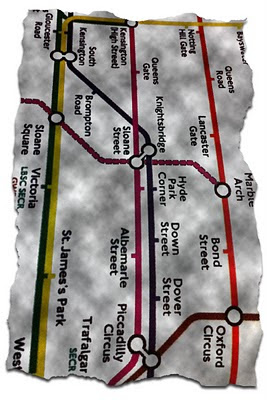

It may not be real but I'm certainly not the only person to have imagined such a Neverwhere, such an Un Lun Dun. There's something about such a subterranean network of tunnels that has fastened hooks in our imaginations since the first tube opened in 1863. Something about that familiar brightly coloured wiring diagram that speaks to us on levels we don't fully comprehend.

They've ruined it now of course. The magic map now lies defaced by the ugly scrawls of Docklands and Overground, a mere parody of its former self.

Harry Beck would not be pleased.

Nevertheless things were very different now. For a start I was growing up. Not only had I recently discovered the allure of spiky women in general and Toyah Willcox in particular which had put an entirely different spin on things, but I'd also moved up into the senior school.

This latter move was an extremely unpleasant one (at some point I will write a comprehensive blog entry explaining why), so suffice to say that I decided to continue concentrating on my inner life and as a result my enthusiasm for all things London Underground remained, albeit in a diminished form.

One of the best things about the location of Cranley Gardens was that it had been on one of the great lost lines that originally flowed outwards from Highgate. Imagine that; I was living in a road that had once had its own tube station but which was now derelict. I even worked out where the station had been.

Right up at the top of Cranley Gardens diagonally opposite one looming corner of Highgate Wood (still dark and primeval to me) and across from number 23 (which would become famous a few years afterwards for very different reasons) lay a garden centre. They were all the rage back then. Behind the garden centre was a sunken path.

The layout and feel of this path was very familiar to me from my earlier explorations of the hidden places in Highgate Wood. This was quite clearly the route of an abandoned railway, the unnatural curve of the path gave it away, the rubble of pumice underfoot. It disappeared off behind the houses through thick trees before rising above them on a viaduct that gave commanding views of East London and Essex. The route was lined with rusty metal signs warning of 50,000 volts amongst the weeds and stanchions that had obviously once carried cables, but like its cousin across in Highgate Wood, this Dism Rly had no actual sleepers or tracks, no real live rail despite the warnings.

Such was the unevenness of ground level in Muswell Hill that even after being so high up the track shortly afterwards found itself looking up at the backs of houses and shops on Muswell Hill Broadway before coming to a end at a pedestrian subway under Muswell Hill itself.

There was no sign of the actual stations themselves and from this point onwards it became difficult to follow the route to the terminus at Alexandra Palace. There was a school in the way for a start. If I wanted more I would have to look elsewhere.

Heading east from Highgate I soon discovered the rest of this ancient route curving round from the junction of Archway Road and Jackson's Lane, another stretch of abandoned railway bed that would one day become known as the Parkland Walk. Through cuttings and across narrow viaducts this route took in Crouch End station, the only place aside from the secret platforms at Highgate that still resembled a railway station. In some ways the discovery and pinning down of the solution to this childhood mystery was the end of the line for me. I could move on, although for years afterwards the route was one of my favourite walks.

But there was one place - in fact there still is one place - that the more mythical Tube has persisted. Inside my head. In dreams. Night dreams, not daydreams.

There's a somnambulant network there, reflecting but somehow far more exciting than the real thing could ever hope to be; in the dreamworld you don't need to get planning permission and as such things are bigger and better. Furthermore, these lines are all part of what appears to be a very consistent dream world (see earlier blog entry Dancing the Dreamscape for more detail of this).

There's a distant version of the western outreaches of the Metropolitan Line that takes days to get to and from. There are vast swathes of tracks filling an entire valley alongside the main route somewhere near Crouch End station, an idealised version of the stillborn branch line I discovered so long ago.

There are versions of the Circle Line in which the tracks run alongside mysterious caverns inhabited by strange manlike creatures; a Victoria Line that somehow manages to run as far south as Luxor in Egypt. And often there are dreams of the retooling of the whole network, vast building works threading myriad extra lines through the congested cats cradle of central London with complex new branches of the District Line sprouting like vines across the barren tubeless wastes of South London.

It may not be real but I'm certainly not the only person to have imagined such a Neverwhere, such an Un Lun Dun. There's something about such a subterranean network of tunnels that has fastened hooks in our imaginations since the first tube opened in 1863. Something about that familiar brightly coloured wiring diagram that speaks to us on levels we don't fully comprehend.

They've ruined it now of course. The magic map now lies defaced by the ugly scrawls of Docklands and Overground, a mere parody of its former self.

Harry Beck would not be pleased.

Crouch End station photo by Steve Way

Comments